English Poetry vs. Arabic Poetry: What's the Difference?

Why the difference is subtle, yet leads to a substantial misunderstandings.

Some time ago, in the depths of the winter blues, a relative of mine and I discussed poetry over tea. Not necessarily the writing portion itself, but everything pertaining to the art of poetry, with a heavy emphasis on the writer's life.

Whether it was the tea, or something in the air, we both were in a well-humored, mirthful mood, and any comment made by the latter was met with laughter by the former. I told of Antarah ibn Shaddad, his origin as a slave and how he subsequently became one of the greatest poets in the pre-Islamic era. How his rise all began with a war his tribesmen were losing, and in an act of desperation, there was a plea for him to aid them and fight. I can only imagine the bombastic side-eye he must have given, the audacity of the request sending my relative and me roaring. But Antarah fought, and though his adventures would be too long to list here (coming soon), he had this to say of his fighting days.

كنت أقدم إذا رأيت الإقدام عزمًا

وأحجم إذا رأيت الإحجام حزمًا

I would advance if I saw that advancing was determination,and I would hold back if I saw that holding back was firmness.

Then there was Qais and Layla, the Romeo and Juliet of the Middle East whose love was written in verses formed from heartache. As in almost all ancient love stories, the two lovers knew no peace from those around them, which led to Layla's arranged marriage and departure from her homeland, to which Qais had this to say:

أَمُرُّ عَلى الدِيارِ دِيارِ لَيلى

أُقَبِّلَ ذا الجِدارَ وَذا الجِدارا

وَما حُبُّ الدِيارِ شَغَفنَ قَلبي

وَلَكِن حُبُّ مَن سَكَنَ الدِيارا

I pass the walls of the house of Layla SometimesI kiss this wall, sometimes I kiss that one

It is not the love of these walls that has infatuated my heart

But the love of who lives within them

No doubt no poetic reminiscence would be complete without mentioning Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian resistance poet who once fell in love with an Israeli woman. While all love stories seem so far away, Mahmoud's tragic tale is still an unhealed wound, fresh as though cut yesterday. Mahmoud, who dedicated his life to Palestine, had this to say of his heartache:

شعرت بأن وطني احتل مرة أخرى

I felt like my homeland was occupied again.

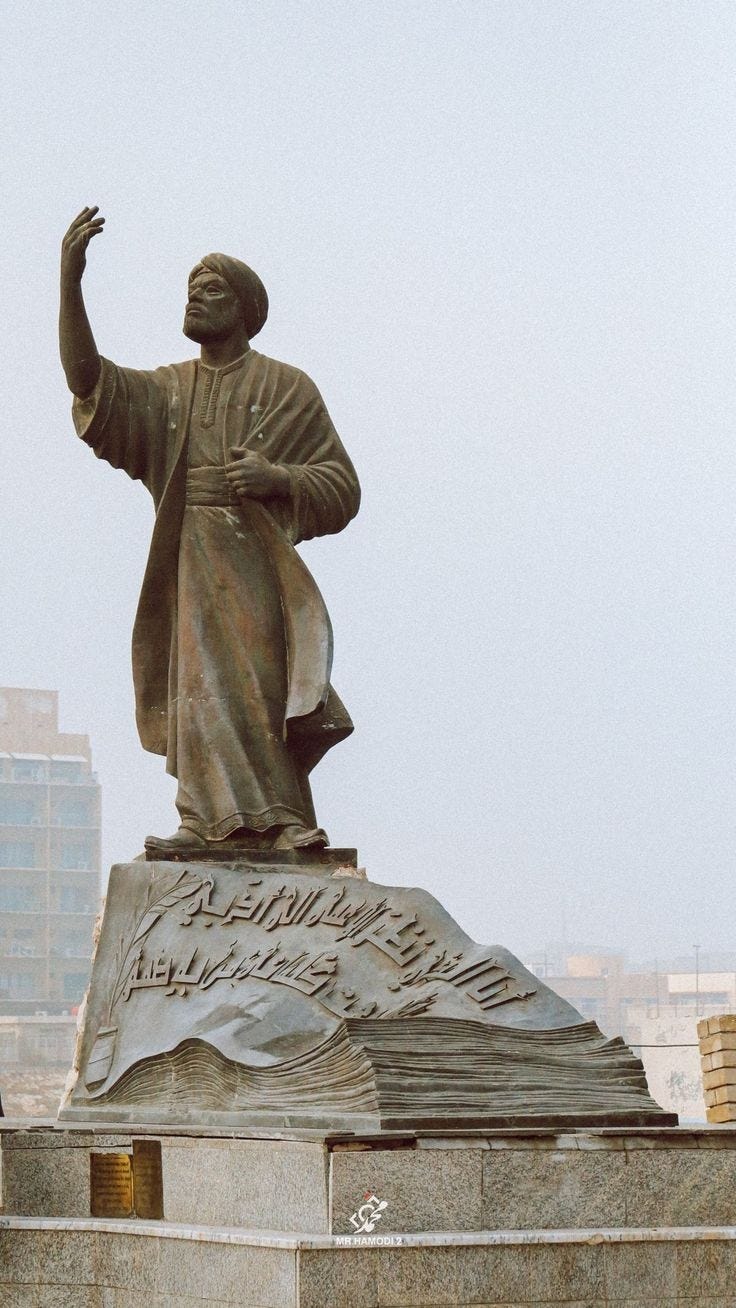

The transition from Qais and Layla, and Mahmoud and Rita, to Al-Mutanabbi, who also wrote love poetry, did us in for good. For he also wrote love poems, not for others, but rather himself, in a form of poetry where one praises his own self and his accomplishments, to which he said a lot. A famous line of his being:

أنا الذي نظر الأعمى إلى أدبي

وأسمعت كلماتي من به صمم

I am the one whose literature is seen by the blindAnd whose words are heard by the deaf.

What of English poetry? They asked next. What of English poetry! Tragedy knows no time zone nor hemisphere, and all that has happened in the East has also befallen the West. I recalled Sylvia Plath, her tragic suicide, and her impact on confessional poetry. Her complex developments after the passing of her father at a young age and the cheating of her husband. And what of her poetry? Yes! Her poetry. I recited what I had memorized.

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Again, we roared with laughter. It would be more accurate had I only listed the first line, because that is all I had managed to see before we lost it once more (which was a miracle by some sense, my ability to remember not being that well). The transition between Arabic poetry to English poetry was so striking it recalled to me prior comments.

"Why read English poetry at all?"

"How do you enjoy that?"

"Arabic poetry is better, I would just stick to it."

I love Sylvia Plath and have read all her work, including The Bell Jar and her unabridged journals, which is precisely why I bring up this poem. I know how much effort goes into her work. I know just how much she has studied (or at least said to do so in her journals), reviewed, altered, and practiced to construct her poetry into her own particular style. An excerpt from her says it all:

Now the moon has undergone a rapid metamorphoses,

made possible by the vague imprecise allusions in the first line, and become a

tulip or crocus or aster bulb, whereupon comes the metaphor: the moon is

"bulbous", which is an adjective meaning fat, but suggesting "bulb", since the

visual image is a complex thing. The verb "sprouts" intensifies the first hint of a

vegetable quality about the moon. A tension, capable of infinite variations with

every combination of words, is created by the phrase "soiled indigo sky". Instead

of saying blatantly "in the soil of the night sky", the adjective "soiled" has a

double focus: as a description of the smudged dark blue sky and again as a

phantom noun "soil", which intensifies the metaphor of the moon being a bulbplanted in the earth of the sky. Every word can be analyzed minutely - from the

point of view of vowel and consonant shades, values, coolnesses, warmths,

assonances and dissonances.

In Arabic, a language with 12 million said words, this overlap of verbs, adjectives, nouns, etc. cannot be found, simply because there is a word that can be found meant precisely for its usage. Soil either means تراب (dirt) or وسخ (dirty), but not both.

Assonance, the repetition of vowel sounds in a sentence or phrase, is another factor used often in poetry that is often overlooked. Not to mention alliteration, the repetition of the same consonant sound in the beginning of words, cacophony, unpleasant sounds to create disorder, or its opposite, euphony, a series of sounds that sound pleasant and create musical harmony.

Sylvia utilized these sound poetic devices in her poetry. How the word sounded was equally important to what it conveyed, and she wrote only in free verse. Now imagine a structured poem and the juggling a poet would need to achieve to balance all aspects. Shakespeare's sonnets are an example of a structured poem which utilizes arrangement and structure of the words. Unlike in free verse, in English sonnets there is a limit to the number of syllables in a verse, that being ten, and the almost impossible task of following an iambic pentameter, as well as perfect rhyme order and achieving line maximum.

If there is one difference between Arabic poetry and English poetry, it’s that Arabic poetry can be enjoyed at surface level, and English poetry is better enjoyed after being studied. For this reason, English poetry is often undermined, mostly because it is misunderstood. Often there are hidden meanings, double meanings, and references that go unnoticed, thus dismissing the poem as a whole. Arabic poetry, of course, is just as difficult with its own set of rules and teachings, but it receives recognition and appreciation, something English poetry cannot be said of. Rather than comparing the two, appreciate them as two separate forms of writing, with one ultimate goal of enjoyment.

I apologize for having not related my Wednesday poetry posts. With the holiday season and life underway, I had underestimated just how much time I would need to construct the posts. That is not to say it won't happen soon, but the series official release will come in the new year. Until then, which of the poets' lives mentioned in the post would you like to hear of first? Let me know and I will do my best to make it possible.

Thank you! Informative and useful to me as I begin to read more Arabic poetry (in translation).

Nice to meet a kindred spirit.