Modern times are conflicting. We have documented letters in the form of text messages that can be accessed from handheld devices at a moment's notice. We have audio recordings in the form of voicemails or messages that can definitively prove or disprove accusations. We live in times where man-made creations are feared more than the Creator of man Himself. People no longer morally object to the immoral; they merely fear the repercussions.

By no means should this conviction be perceived in a negative light. With so many tools at one’s disposal, there remains considerable means to fight for social change. Cellphone cameras to document, keyboards to type, social media to spread the message. Nonetheless, there remains a flaw. A side effect of sorts born from the black-and-white foundation upon which the modern world is built. If everything is so easily proven, what becomes of cases that are impossible to prove? The cases with no definitive answer, no tangible evidence to provide, whose outcome is mere speculation formed in the back of one’s mind; either they're truthful or they’re not. And as for the subjects of these speculations, who are they to speak to? They remain pondering the facts, unable to tell anyone, because really, who would believe them?

Such is the case with matters of discrimination. Rarely does one receive blatant rejection based on sex, color, age, ethnicity, etc. The rejection seeps through like mist. Always subtle. Always unnoticed. Another bitter pill to swallow. A pill to keep down and quiet about.

Those of us who’ve consumed such pills—or had the pill consume us—are always left lingering with its aftertaste. I swallowed such a pill a couple of months ago, and its aftertaste has only grown stronger—overpowering, lingering in my thoughts. I must write! I knew, and I write now, yet I tell this story with the knowledge that though I can’t prove it for certain, I felt it for certain.

It was a Wednesday, and I had a virtual interview alongside other applicants. And my laptop had died. I was at the public library finalizing some writing when I remembered the interview. "Curse me for forgetting," I said to myself—ironically, this line I remember. And so, with no laptop and no time to get home, I joined through my phone, 10 minutes late. Having not heard the first interview question, I inferred my response from the applicants' answers and delivered it mechanically. I was the only one without my camera on. Having joined late and being characteristically introverted, I kept it off—something I knew was not allowed, something I did anyway. Keep this in mind; it’s pertinent to the story. When the second interview question came, I was even more unprepared than for the first (which I believe to have been a self-introduction). This time, it was a direct question with a definite answer. I could see pens in hand, fingers typing, as everyone prepared for the question. I, standing by the library exit with my phone in hand, pretended it was a call so as not to disturb others. I could do little more than walk in laps and mentally prepare my answer. Using the Grecian way of rhetoric, my persuasive method of speaking that past teachers have always complimented—"I can see you being a lawyer" (ha! If only they could see me now)—and the skills developed by being a reader, I gave my answer and could see a smile form on the interviewer's face.

By now, dear reader, I know what thoughts you've formed. Are you sure your rejection was based on discrimination? You came late, missed the first question, had your camera off, and barely prepared for the second question. You were bound for rejection. This I knew. This I was assured of. Until I saw that I had made it to the second interview. By the grace of God, it was a miracle! Only I and another applicant had made it to the second portion. Attached to the email was a PDF, a script to be memorized—four pages long. The next day was the interview. Were they insane?? I was no actor to be memorizing lines, but memorizing lines I must! Maybe, I thought, this was a test to see who really wanted the job. Who would pull through and prepare. And so at once, I sat and began the memorization.

The fateful day of the interview had come. Unlike the first time, this time I was prepared. If by a miracle I had passed the first step, the second should be a piece of cake. Or so I thought. I had my camera on, better-prepared answers, more experience than the opposing applicant, and more skills to bring—including my bilingualism, an asset for this job. I even asked questions following the interview (something I had been recommended to do after a previous rejection) and left no question unanswered (another recommendation). We were to receive our acceptance emails the next day if hired. I waited, and nothing came. Not the next day. Not the day after. Not even the week after. I had been rejected.

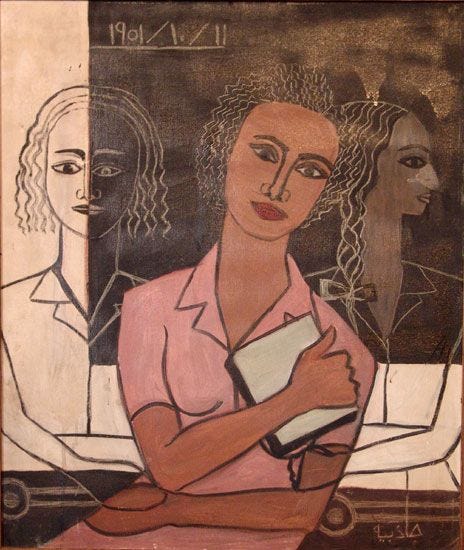

Impossible! I do not say this to boast about myself—that I deserved the role or was the perfect candidate. On the contrary, though it all went smoothly, I was average in every way. I say this because my opposing applicant was just plain bad. She had no skills to bring. No experience in the field (which I did). And the cherry on top was her script reading—which I had perfected—was not only broken but incorrectly delivered. (Instead of saying "half of something," she would say "the full of something," a subtle difference that changed the course of the whole script. Something I noticed. I wonder if the interviewer did.) But she had a look. Pale skin. Straight hair. Whereas I was plainly ethnic. And then it occurred to me, with the power of retrospect, that everyone in the first interview had been ethnic. Mostly Indian, a peppering of African, Desi, and some older adults. But when I joined the first interview, no one saw me. I had no accent—something I note because it often gives a semblance of ethnicity. Now that I review it, the impossible part was my acceptance into the second interview to begin with! And when I had joined and revealed myself through the camera, I was now part of the rejected group. The one thought I revisit over and over is the camera. I should have kept it off. I had always been complimented for my well-spoken voice. My use of rhetoric. My stoic style of speaking. I should have just stuck to that.

There is an Arabic proverb that goes, "To cut one's neck is better than cutting their livelihood [income]" (قطعُ الأعناق ولا قطع الأرزاق). I've heard and reheard it when pardoning unforgivable work mistakes. When forgiving illegal activity from an official. It is why acts such as bribery or nepotism go unaccounted for—not because they are not caught, but because of the belief that a warning is better than firing someone. I keep this quote in mind when analyzing the other applicant. It is not her fault I was rejected. It was not even her intention to use her favoured features against my ethnic ones. Though the urge to reach out and discuss certain issues clings to my heart, I remember this quote, and I choose not to take any rash actions that would jeopardize her livelihood. I just wish others would remember to do the same for me.

I had written this piece back in February and let it gather dust in my drafts. Since then, similar occurrences—even more striking than the one I shared—have taken place. I’ve since learned to avoid any application that includes phrases like "face of our company" or "first point of contact with our customers." That decision has served me well. I share this anecdote simply as a piece of honest testimony.

There is a profound irony in being perceived as a Westerner in the Middle East, and as a Middle Easterner in the West. These are the lived realities of someone who fits both molds, yet fully belongs to neither.

If you found value in today’s essay and would like to read more, do let me know. Could you relate to this story? (Though, dear reader, I hope you do not.) And is it within the right of the "other" to deny someone like me? After all, walk into a dental clinic and you’ll find that most of the staff look alike—rarely, if ever, does an outlier appear. I welcome your thoughts and any commentary below.